InvenTeams turns students into inventors

In 2023, students from Calistoga Junior/Senior High School in California entered a year-long invention project run by the Lemelson-MIT Program. Tasked with finding problems to solve in their community, the students settled on an invention to keep firefighters and agricultural workers cool in hot working conditions.

Over the next 12 months, the students learned more about the problem from the workers, developed a prototype cooling system, and filed a patent for their invention. After presenting their solution at the program’s capstone Eurekafest event at MIT, the students were invited to the California State Capitol to share their work with lawmakers, and they went on to be selected as finalists in the student SXSW Innovation Awards.

For 20 years, the Lemelson-MIT InvenTeams Grant Initiative has inspired high school students across the country by supporting them through an extracurricular invention program that culminates in presentations on MIT’s campus each spring. The students select their own problems and invent their own solutions, receiving $7,500 in grants from Lemelson-MIT, along with mentorship, technical consultation, and more support to turn their ideas into reality.

In total, high school InvenTeams have been granted 19 U.S. patents since the program’s start, with many more teams, like the one from Calistoga, continuing work on their inventions after the program. Students often report an increased sense of confidence and interest in STEM subjects following their InvenTeams experience. In some cases, that new mindset changes students’ life trajectories.

“In a traditional school setting, students don’t always get the chance to show what they can do,” says Calistoga High School teacher Heather Brooks, who sponsored the 2023 team. “I was blown away by the students’ power and creativity.”

Turning students into inventors

The Lemelson Prize program started in 2004 with one $500,000 award given to a prolific inventor each year and smaller prizes given to inventor teams from MIT. In 2006, following a National Science Foundation report on the best ways to foster and support inventors, the program started awarding smaller grants to teams of high school students across the country.

“[Program founder] Jerome Lemelson wanted to inspire young people to become inventors and had a deep belief that America’s strength and innovation was driven by invention,” says Lemelson-MIT Executive Director Stephanie Couch. “He wanted young people to celebrate inventors like they celebrate rock stars and football players.”

When Couch arrived at MIT nine years ago, her research showed that giving small grants to younger students was the most successful way to increase students’ interest in STEM subjects.

Each year, the InvenTeams program receives between 50 and 80 applications from student teams across the country. From there, 20 to 30 teams are selected for Excite Awards. Those teams submit an in-depth application in which they describe the problem they’re solving, conduct patent research, and share early ideas for their solution. They also outline plans for community engagement, budget allocation, and additional background research.

Judges with a range of expertise select the finalists, who submit monthly updates throughout the year. Teams also meet with the community members they are inventing solutions for regularly.

“We see invention as a practice in empathy,” says Edwin Marrero, the interim invention education manager of the Lemelson-MIT program. “When you’re inventing, you’re inventing for somebody — and we like to say you’re inventing with somebody. Students learn to communicate and work in their communities. It’s a good skill to learn early in life.”

The final event at MIT, dubbed Eurekafest, is held every June. It features live presentations at the Stata Center that are open to the public and allow the students to showcase their inventions. Students stay in MIT dormitories for a few days leading up to the presentations and participate in a series of networking opportunities.

“The presentations are my favorite part, because people are peppering students with questions, and their depth of understanding, along with the confidence they project, is totally unlike anything you’ve ever seen from a high schooler,” Couch says.

This year’s teams presented ways to detect contamination in drinking water, help visually impaired people communicate, treat groundwater for use in agriculture, and more. Finalist teams hailed from Lubbock, Texas; Edison, New Jersey; Nitro, West Virginia, and — for the first time in the program’s history — MIT’s backyard of Cambridge, Massachusetts. The team from Cambridge invented a communication device for rowers on crew teams so they can hear from their coaches. They filed a patent for their invention.

“We’ve learned from our research that this one-year program really does transform the students’ perceptions of themselves, what they’re capable of, and what they’ll do next,” Couch says. “Also, by letting them pick what problem they want to solve and for whom they want to solve it, we’re giving them agency and tapping into that intrinsic motivation in life — to find meaning and purpose. How often in school do you get to find a problem versus being told which one to work on?”

Scaling invention education

There are many stories about the impact of the InvenTeam program on students. In 2016, a team of students on the autism spectrum developed a treadmill device and app to detect lameness in cows on dairy farms — a way to catch injury or disease in the animals. The students filed a patent for the device, which cost far less than other solutions on the market.

In 2018, a team from Garey High School in California developed a sensor device to help monitor foot health in diabetic patients and prevent amputations.

“Our school is one of the lowest-performing academically, and 99 percent of our students are low income,” says Antonio Gamboa, the school district’s former science department chair. “Before the Lemelson-MIT InvenTeams grant, district administrators said they didn’t have money to support science. Once they saw what these students could do, that turned around — not just in our school, but across the district.”

The InvenTeams program has been so successful the Lemelson-MIT program created a membership program, called Partners in Invention Education, to help many more schools adopt invention education. The curriculum stretches from kindergarten all the way to the first two years of college.

“As a middle school math teacher in New York City Public Schools, I noticed kids are falling out of love with these STEM subjects at an early age,” Marrero says. “I think a big reason for that is it’s not taught in a way that meaningful to them. There often aren’t real-world applications in lessons. Lemelson-MIT’s invention education makes STEM subjects relevant to kids. They’re the drivers of the learning. They might discover they need math or science skills to solve the problem they’re working on, and it creates a different level of motivation.”

Latest MIT Latest News

- 3 Questions: Applying lessons in data, economics, and policy design to the real worldGevorg Minasyan MAP ’23 draws on experiences in MIT’s Data, Economics, and Design of Policy MicroMasters and master’s programs to shape policymaking at the Central Bank of Armenia.

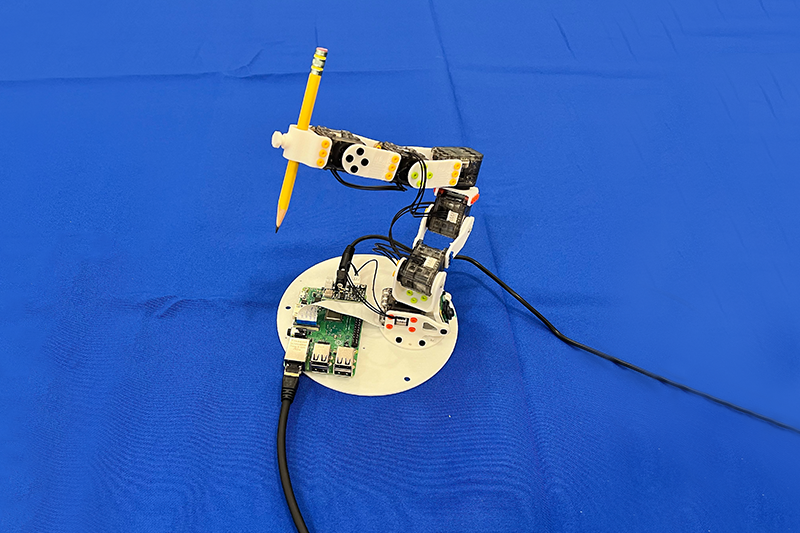

- Robot, know thyself: New vision-based system teaches machines to understand their bodiesNeural Jacobian Fields, developed by MIT CSAIL researchers, can learn to control any robot from a single camera, without any other sensors.

- Pedestrians now walk faster and linger less, researchers findA computer vision study compares changes in pedestrian behavior since 1980, providing information for urban designers about creating public spaces.

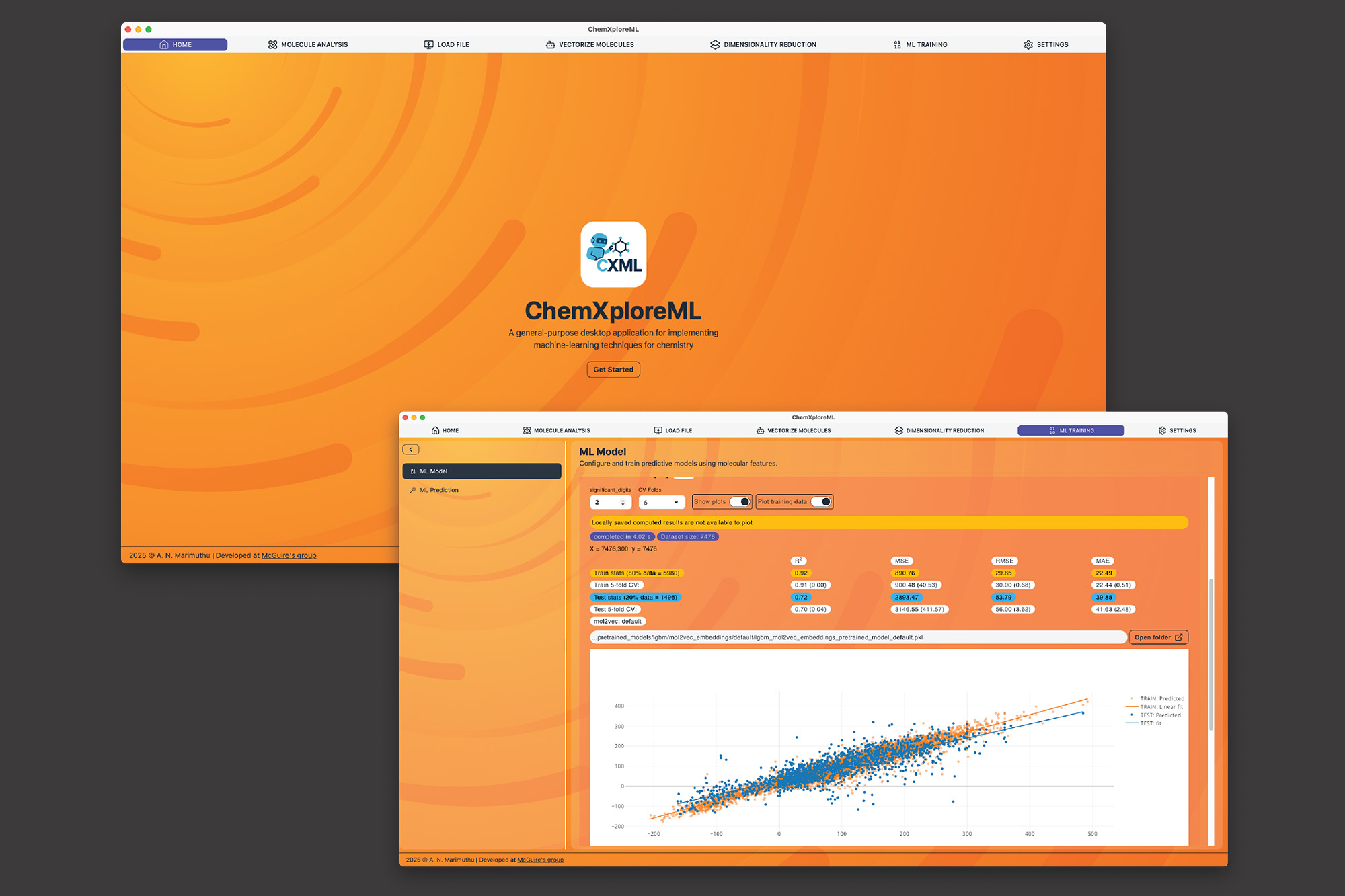

- New machine-learning application to help researchers predict chemical propertiesChemXploreML makes advanced chemical predictions easier and faster — without requiring deep programming skills.

- Scientists apply optical pooled CRISPR screening to identify potential new Ebola drug targetsCombining powerful imaging, perturbational screening, and machine learning, researchers uncover new human host factors that alter Ebola’s ability to infect.

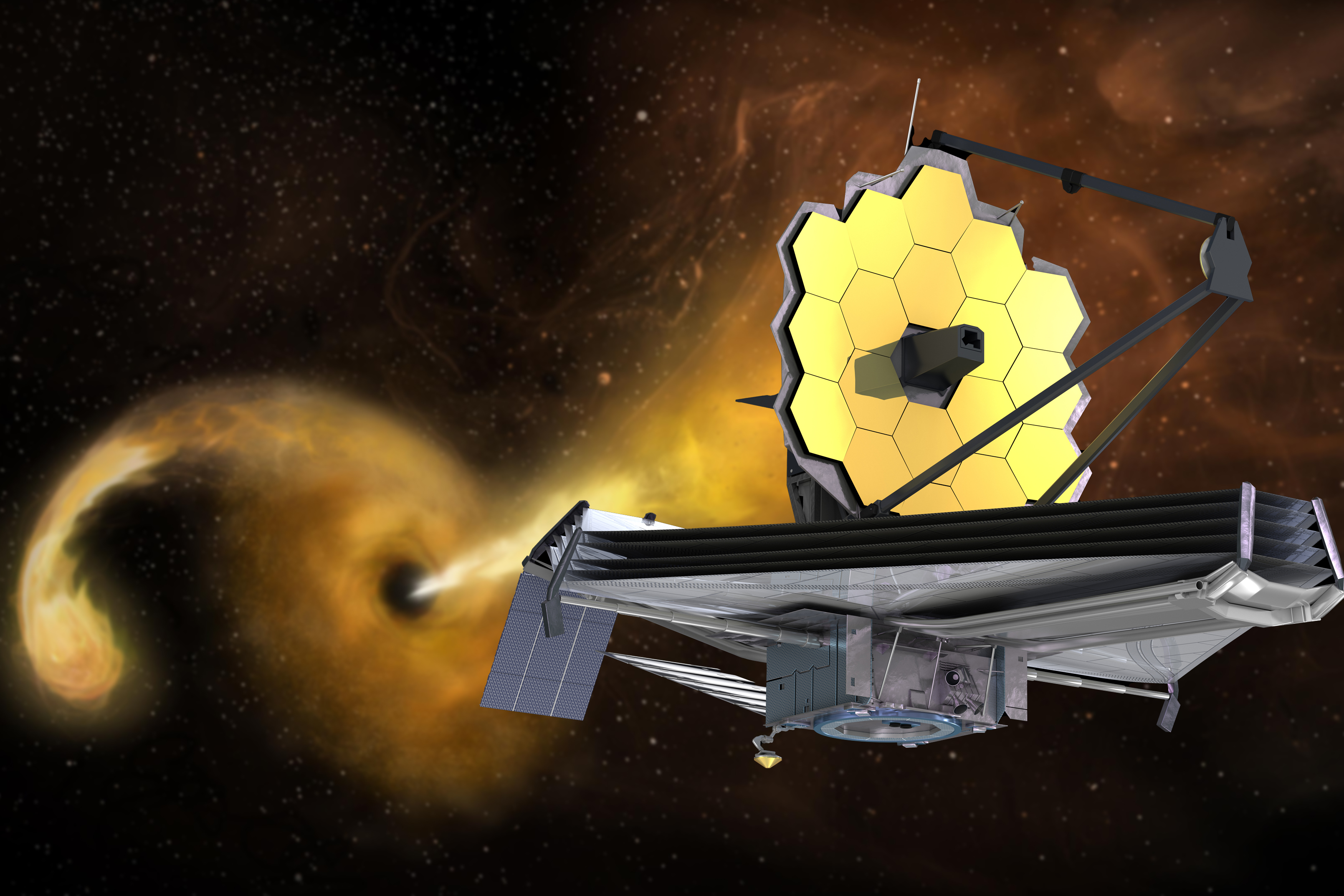

- Astronomers discover star-shredding black holes hiding in dusty galaxiesUnlike active galaxies that constantly pull in surrounding material, these black holes lie dormant, waking briefly to feast on a passing star.