Study reveals the role of geography in the opioid crisis

The U.S. opioid crisis has varied in severity across the country, leading to extended debate about how and why it has spread.

Now, a study co-authored by MIT economists sheds new light on these dynamics, examining the role that geography has played in the crisis. The results show how state-level policies inadvertently contributed to the rise of opioid addiction, and how addiction itself is a central driver of the long-term problem.

The research analyzes data about people who moved within the U.S., as a way of addressing a leading question about the crisis: How much of the problem is attributable to local factors, and to what extent do people have individual characteristics making them prone to opioid problems?

“We find a very large role for place-based factors, but that doesn’t mean there aren’t person-based factors as well,” says MIT economist Amy Finkelstein, co-author of a new paper detailing the study’s findings. “As is usual, it’s rare to find an extreme answer, either one or the other.”

In scrutinizing the role of geography, the scholars developed new insights about the spread of the crisis in relation to the dynamics of addiction. The study concludes that laws restricting pain clinics, or “pill mills,” where opioids were often prescribed, reduced risky opioid use by 5 percent over the 2006-2019 study period. Due to the path of addiction, enacting those laws near the onset of the crisis, in the 1990s, could have reduced risky use by 30 percent over that same time.

“What we do find is that pill mill laws really matter,” says MIT PhD student Dean Li, a co-author of the paper. “The striking thing is that they mattered a lot, and a lot of the effect was through transitions into opioid addiction.”

The paper, “What Drives Risky Prescription Opioid Use: Evidence from Migration,” appears in the Quarterly Journal of Economics. The authors are Finkelstein, who is the John and Jennie S. MacDonald Professor of Economics; Matthew Gentzkow, a professor of economics at Stanford University; and Li, a PhD student in MIT’s Department of Economics.

The opioid crisis, as the scholars note in the paper, is one of the biggest U.S. health problems in recent memory. As of 2017, there were more than twice as many U.S. deaths from opioids as from homicide. There were also at least 10 times as many opioid deaths compared to the number of deaths from cocaine during the 1980s-era crack epidemic in the U.S.

Many accounts and analyses of the crisis have converged on the increase in medically prescribed opioids starting in the 1990s as a crucial part of the problem; this was in turn a function of aggressive marketing by pharmaceutical companies, among other things. But explanations of the crisis beyond that have tended to fracture. Some analyses emphasize the personal characteristics of those who fall into opioid use, such as a past history of substance use, mental health conditions, age, and more. Other analyses focus on place-based factors, including the propensity of area medical providers to prescribe opioids.

To conduct the study, the scholars examined data on prescription opioid use from adults in the Social Security Disability Insurance program from 2006 to 2019, covering about 3 million cases in all. They defined “risky” use as an average daily morphine-equivalent dose of more than 120 milligrams, which has been shown to increase drug dependence.

By studying people who move, the scholars were developing a kind of natural experiment — Finkelstein has also used this same method to examine questions about disparities in health care costs and longevity across the U.S. In this case, in focusing on the opioid consumption patterns of the same people as they lived in different places, the scholars can disentangle the extent to which place-based and personal factors drive usage.

Overall, the study found a somewhat greater role for place-based factors than for personal characteristics in accounting for the drivers of risky opioid use. To see the magnitude of place-based effects, consider someone moving to a state with a 3.5 percentage point higher rate of risky use — akin to moving from the state with the 10th lowest rate of risky use to the state with the 10th highest rate. On average, that person’s probability of risky opioid use would increase by a full percentage point in the first year, then by 0.3 percentage points in each subsequent year.

Some of the study’s key findings involve the precise mechanisms at work beneath these top-line numbers.

In the research, the scholars examine what they call the “addiction channel,” in which opioid users fall into addiction, and the “availability channel,” in which the already-addicted find ways to sustain their use. Over the 2006-2019 period, they find, people falling into addiction through new prescriptions had an impact on overall opioid uptake that was 2.5 times as large as that of existing users getting continued access to prescribed opiods.

When people who are not already risky users of opioids move to places with higher rates of risky opioid use, Finkelstein observes, “One thing you can see very clearly in the data is that in the addiction channel, there’s no immediate change in behavior, but gradually as they’re in this new place you see an increase in risky opioid use.”

She adds: “This is consistent with a model where people move to a new place, have a back problem or car accident and go to a hospital, and if the doctor is more likely to prescribe opioids, there’s more of a risk they’re going to become addicted.”

By contrast, Finkelstein says, “If we look at people who are already risky users of opioids and they move to a new place with higher rates of risky opioid use, you see there’s an immediate increase in their opioid use, which suggests it’s just more available. And then you also see the gradual increase indicating more addiction.”

By looking at state-level policies, the researchers found this trend to be particularly pronounced in over a dozen states that lagged in enacting restrictions on pain clinics, or “pill mills,” where providers had more latitude to prescribe opioids.

In this way the research does not just evaluate the impact of place versus personal characteristics; it quantifies the problem of addiction as an additional dimension of the issue. While many analyses have sought to explain why people first use opioids, the current study reinforces the importance of preventing the onset of addiction, especially because addicted users may later seek out nonprescription opioids, exacerbating the problem even further.

“The persistence of addiction is a huge problem,” Li says. “Even after the role of prescription opioids has subsided, the opioid crisis persists. And we think this is related to the persistence of addiction. Once you have this set in, it’s so much harder to change, compared to stopping the onset of addiction in the first place.”

Research support was provided by the National Institute on Aging, the Social Security Administration, and the Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research.

Latest MIT Latest News

- Battery-powered appliances make it easy to switch from gas to electricFounded by Sam Calisch SM ’14, PhD ’19, Copper’s electric kitchen ranges plug into standard wall outlets, with no electrical upgrades required.

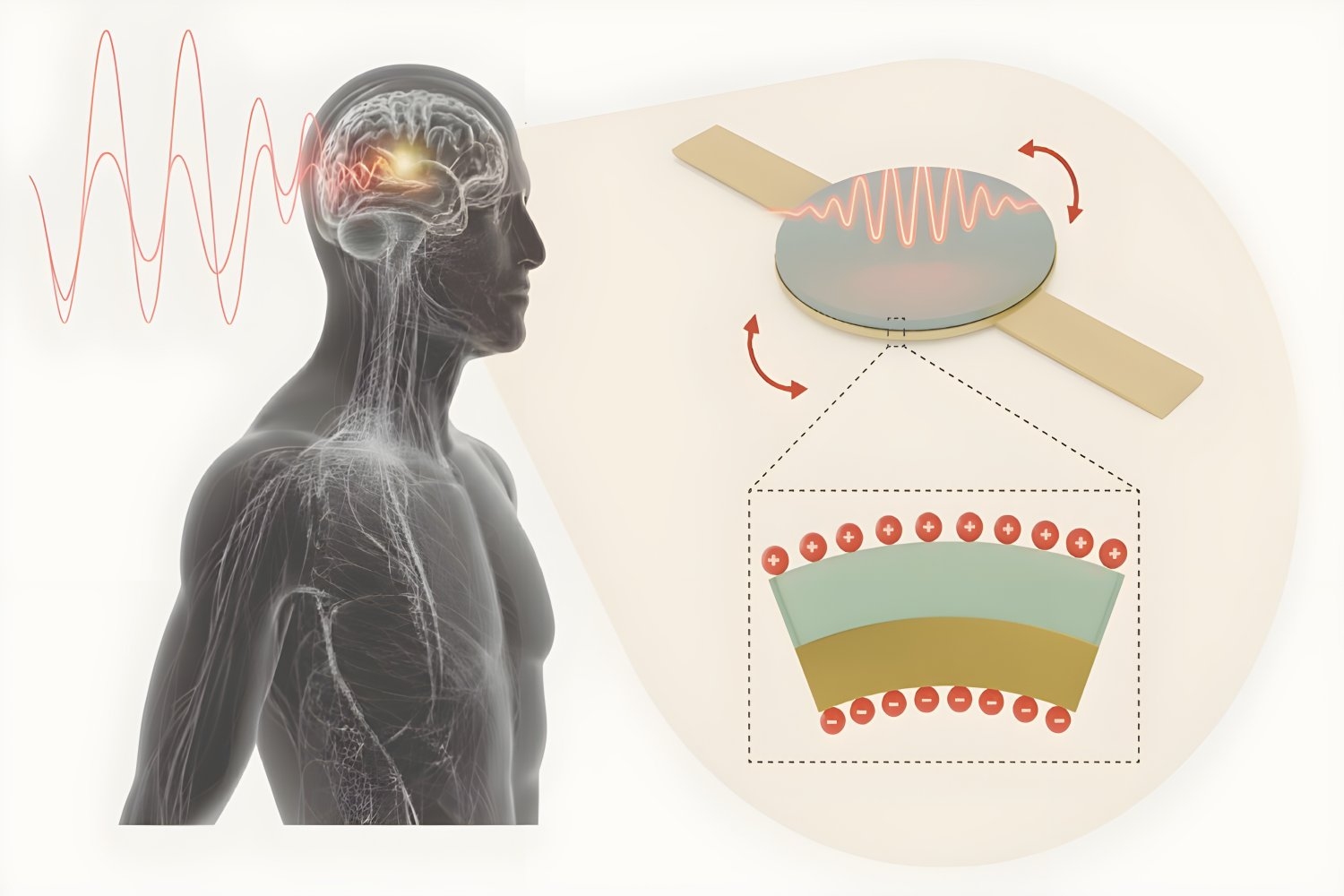

- Injectable antenna could safely power deep-tissue medical implantsThe technology would allow battery-free, minimally invasive, scalable bioelectronic implants such as pacemakers, neuromodulators, and body process monitors.

- Burning things to make thingsSili Deng, the Doherty Chair in Ocean Utilization and associate professor of mechanical engineering at MIT, is driving research into sustainable and efficient combustion technologies.

- Study: Identifying kids who need help learning to read isn’t as easy as A, B, CWhile most states mandate screenings to guide early interventions for children struggling with reading, many teachers feel underprepared to administer and interpret them.

- This is your brain without sleepNew research shows attention lapses due to sleep deprivation coincide with a flushing of fluid from the brain — a process that normally occurs during sleep.

- New method could improve manufacturing of gene-therapy drugsSelective crystallization can greatly improve the purity, selectivity, and active yield of viral vector-based gene therapy drugs, MIT study finds.